Chapter 8 of Trellis And the Vine

Chapter 8 of Trellis And the Vine

Hi folks

Here is the next chapter in our church training section.

Every Blessing as we chat about church structures enabling church ministry on Thursday night.

Chapter 8.

Why Sunday sermons are necessary but

not sufficient

We've come to the point in the flow of our argument where we need to

pause and consider in more detail how the model of training and growth we

are proposing collides with the reality of our existing church structures and

models and practices. Because collide it will. By far the greatest obstacle to

rethinking and reforming our ministries is the inertia of tradition—whether

the long-held traditions of our denominations and churchmanship, or the more

recent traditions of the church growth movement that have become a kind of

unspoken orthodoxy in many evangelical churches.

We will get to the somewhat alarming proposition contained in this

chapter's title in due course, but first let's look at two very common

approaches to pastoral ministry, and then contrast them with the approach of

this book. Now of course these common approaches are stereotypes, and

cannot reflect the multi-faceted reality of ministry in all its variety. All the

same, we trust that you can recognize the structures and tendencies reflected

in the descriptions, and make adjustments for your own situation accordingly.

There are three approaches or emphases we wish to examine, which we

will call:

• the pastor as service-providing clergyman

• the pastor as CEO

• the pastor as trainer.

The pastor as service-providing clergyman

In this way of thinking about church life and ministry, the pastor's role is

to care for and feed the congregation. In this sense, he is a professional

clergyman (whether or not he is called a 'clergyman'), and there is an

expectation on the part of both congregation and pastor that he is paid to fulfil

certain core functions:

• to feed the flock through his Sunday sermons and administration of the

sacraments

• to organize and run the Sunday gathering, which is seen as a time of

worship for the congregation

• to put on various occasional services for different purposes, such as

baptisms, weddings and possibly guest services

• to personally counsel congregation members, especially in times of

crisis.

This is the classic Reformed-evangelical model of an ordained minister

shepherding the flock given to him by Christ. And it has great strengths:

• It rightly puts regular preaching of the word at the centre of the

ministry.

• It gathers the whole congregation as a family on Sunday for prayer,

praise and preaching.

• The occasional services provide opportunities for outreach.

• The pastor cares for his people in times of crisis.

However, there are also very real (and obvious) disadvantages with this

approach. For a start, the ministry that takes place in the congregation will be

limited to the gifts and capacity of the pastor: how effectively he preaches,

and how many people he can personally know and counsel. In this model, it

becomes very difficult for the congregation to grow past a given ceiling

(usually between 100 and 150 regular members).

Perhaps the most striking disadvantage of this way of thinking about

ministry is that it feeds upon and encourages the culture of 'consumerism'

that is already rife in our culture. It perfectly fits the spirit of our age

whereby we pay trained professionals to do everything for us rather than do

it ourselves—whether cleaning our car, ironing our shirts, or walking our

dog. The tendency is for Christian life and fellowship to be reduced to an

hour and a quarter on Sunday morning, with little or no relationship, and very

little actual ministry taking place by the congregation themselves. In this sort

of church culture, it becomes very easy for the congregation to think of church

almost entirely in terms of 'what I get out of it', and thus to slip easily into

criticism and complaint when things aren't to their liking.

Even the good practice of pastoral counselling can become focused on

'me' being cared for by the pastor—such that if the assistant minister visits

instead, this is not seen as adequate: "The pastor only sent him because he

couldn't be bothered coming himself".

None of this is simply to blame the 'consumer'! For all its historic

strengths, the professional pastor-as-clergyman approach speaks loud and

clear to church members that they are there to receive rather than to give. As

a model, it tends to produce spiritual consumers rather than active disciples

of Christ, and very easily gets stuck in maintenance mode. Outreach or

evangelism, both for individual congregation members and the church as a

whole, is down the list.

In many respects, this first way of thinking about pastoral ministry

reflects the culture and norms of a different world—the world of 16th- and

17th-century Christianized nations, in which the whole community was in

church, and in which the pastor was one of the few with sufficient education

to teach.

The pastor as CEO

In many respects, the 'church growth movement' of the 1970s and 80s

was a direct response to the traditional Reformed-evangelical view of

ministry and church life. People saw some of the disadvantages that we've

outlined and began to think about how they could be addressed. Speaking in

very broad generalizations, the result was a number of key shifts:

• The pastor was still the professional clergyman, but his role became

more focused on leading the congregation as an organization with

particular goals; he was still a preacher and a pastoral serviceprovider,

but he was also now a managerial leader responsible for

making all these things happen on a larger scale. If there was going to be

growth, then the pastor had to learn the difference between running a

corner shop as a sole trader and managing a department store with

numerous staff and a range of services.

• The focus of Sunday shifted towards an 'attractional' model, with the

kind of music, decor and preaching that would be attractive to visitors

and newcomers. If the church was to grow, its 'shopfront' needed to be

much more appealing to the 'target market'. It sounds tawdry when put

like this, but for many churches it was profoundly gospel-centred. It

stemmed from a godly desire to remove unnecessary cultural obstacles

to the hearing of God's word, and to make sure that the only thing weird,

offensive or strange about church was the gospel itself.

• Instead of occasional services, the church growth movement spawned

a revolution of programs and events, both for church members and for

outsiders—everything from evangelistic courses and programs, to

outreach events designed to be attractive to the non-Christian friends of

the congregation, to seminars and programs to help congregation

members with different aspects of their lives (how to raise children,

how to deal with depression, and so on).

• In a church of 500 (rather than 150), how could individual members be

known, cared for, prayed for and helped in times of crisis? Individual

counselling by pastoral staff (let alone the senior pastor) was

logistically impossible, especially given the range of other programs

and activities happening. The answer was the rise of the small home

group, in which members could have a set of personal relationships in

which they could be known and cared for.

One of the key strengths and advantages of the church growth approach

has been its promotion of congregational involvement. This is one of the key

insights of the movement—that if you want someone to join your

congregation and feel part of the place, they need to have something to do.

Church growth research told us that if you found someone a role or job or

opportunity for personal involvement in some ministry within the first six

months of them being at your church, then your chances of retaining that

person as a long-term member massively improved.

The other key strength of the 'church growth' approach is its recognition

that if a congregation is to grow numerically, more work will need to be put

into the trellis. As the cliché goes, the pastor will have to spend less time 'in

the business' and more time 'on the business'. This is simply an inevitable

function of organizational growth and change, and 'church growth' thinking

has helped many pastors to face these challenges of leadership.

There is no doubt that many churches have grown in the past 30 years

through successfully applying 'church growth' principles. It has enabled

churches to grow past 150, and to promote a more active involvement of

congregation members in various church groups, activities and programs.

The downside has been that for all the growth in numbers and

involvement, many 'church growth' churches have also accepted the

consumerist assumptions of our society. Success has been achieved by

providing a more attractive and broadly appealing 'product', but the result is

not always more prayerful ministry of the word, and thus more real spiritual

growth. Lots of people are involved and cared for and receiving help in their

lives, but are people growing as disciples and in mission?

Willow Creek Community Church recently discovered this after 20 years

at the forefront of the church growth movement. In a detailed survey of their

members, the Willow Creek staff discovered that despite running one of the

slickest and most well-organized churches in America—with superb

structures, high-quality music and drama, and an impressive level of

involvement of members in all manner of small groups and activities—

personal spiritual growth as disciples was not happening.[1]

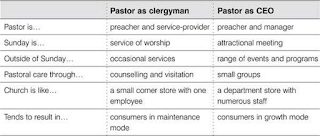

We could represent these two approaches in a table like this:

The pastor as trainer

We have been arguing from the Bible that:

• genuine spiritual growth only comes as the Holy Spirit applies the

word of God to people's hearts

• all Christians have the privilege and responsibility to prayerfully

speak the word of God to each other and to non-Christians, as the means

by which God gives this growth.

If these two foundational propositions are true, then we need a different

mental picture of church life and pastoral ministry—one in which the

prayerful speaking of the word is central, and in which Christians are trained

and equipped to minister God's word to others. Our congregations become

centres of training where people are trained and taught to be disciples of

Christ who, in turn, seek to make other disciples.

• In this way of thinking, the pastor is a prayerful preacher who shapes

and drives the entire ministry through his biblical, expositional

preaching. This is essential and foundational. But crucially, the pastor is

also a trainer. His job is not just to provide spiritual services, nor is it

his job to do all of the ministry. His task is to teach and train his

congregation, by his word and his life, to become disciple-making

disciples of Jesus. There is a radical dissolution, in this model, of the

clergy-lay distinction. It is not minister and ministered-to, but the pastor

and his people working in close partnership in all manner of word

ministries.

• Adding this training emphasis greatly enhances what we do in our

Sunday gatherings, because it builds and grows the gospel maturity of

those who attend. We are training people to be contributors and

servants, not spectators and consumers. The congregation becomes a

gathering of disciple-making disciples in the presence of their Lord—

meeting with him, listening to his word, responding to him in repentance

and worship and faith, and discipling one another. The congregational

gathering becomes not only a theatre for ministry (where the word is

prayerfully spoken) but also a spur and impetus for the worship and

ministry that each disciple will undertake in the week to come.

• Where the pastor is a trainer, there will be a focus on people

ministering to people, rather than on structures, programs and events.

Evangelism will take place as disciples reach out to the people around

them: in their homes, their extended families, their streets, their

workplaces, their schools, and so on. Events and programs and guest

services will still be useful structures to focus people's efforts and

provide opportunities to invite friends, but the real work of prayerful

evangelism will take place as the disciples do it themselves. Taking our

example from the previous chapter, it will happen as Don takes the time

to get to know Bob, and then offers to read through one of the Gospels

with him.

• Pastoral care, in this approach, is also founded on disciples being

trained to care for and disciple other Christians. Small groups may be

utilized as one convenient structure in which this may happen, but the

structure itself will not make it happen. Our goal should not simply be to

'get people into small groups'. Unless Christians are taught and trained

to meet with each other, to read the Bible and pray with each other, and

to urge and spur one another on to love and good works, the small-group

structure will not be effective for spiritual growth. People may get to

know each other in small groups, feel a sense of togetherness and

community, develop warm friendships, and be more bound in to regular

attendance and involvement in the church as a result—but none of these

things amounts to growth in the gospel. It's very possible for a great

deal of the personal encouragement and discipling work in a

congregation to be done one to one, without any involvement in

structured small groups.[2]

The 'pastor-as-trainer' approach contrasts with our other two models

like this:

At this point, it is worth repeating the caveats made earlier in this chapter

(in case they have faded from memory). We are unavoidably dealing with

straw men and stereotypes in this discussion. No particular church will be a

perfect example of any one of these approaches or emphases; there will be

massive individual variation. Indeed, you may look at your own congregation

and recognize it as a strange amalgam of two or more!

All the same, as a thought experiment, delineating these three approaches

is helpful. The tendencies and traditions are recognizable, as are the

consequences.

The insufficient sermon

Perhaps the best way to sharpen what we are arguing for in this chapter is

to say that Sunday sermons are necessary but not sufficient. This may sound

like heresy to some of our readers, and in one sense we hope it does sound a

bit shocking. Are we de-valuing preaching? Surely godly, faithful expository

sermons accompanied by prayer are all that is really required for the

building of Christ's church?

Sermons are needed, yes, but they are not all that is needed. Let's be

absolutely clear: the preaching of powerful, faithful, compelling biblical

expositions is absolutely vital and necessary to the life and growth of our

congregations. Weak and inadequate preaching weakens our churches. As the

saying goes, 'sermonettes produce Christianettes'. Conversely, clear, strong,

powerful public preaching is the bedrock and foundation upon which all

other ministry in the congregation is built. The sermon is a rallying call. It is

where the whole congregation can together feed on God's word and be

challenged, comforted and edified. The public preaching ministry is like a

framework that sets the standard and agenda for all the other word ministries

that take place. We do not want to see less emphasis on preaching or less

effort go into preaching! On the contrary, we long for more godly, gifted

Bible teachers who will set congregations on fire with the power of the

preached word.

To say that sermons (in the sense of Bible expositions in our Sunday

gatherings) are necessary but not sufficient is simply to stand on the

theological truth that it is the word of the gospel that is sufficient, rather than

any one particular form of its delivery. We might say that the speaking of the

word of the gospel under the power of the Spirit is entirely sufficient—it's

just that on its own, the 25-minute sermonic form of it is not.

We say this because the New Testament compels us to. As we have

already seen, God expects all Christians to be disciple-makers by prayerfully

speaking the word of God to others—in whatever way and to whatever extent

that their gifting and circumstances allow. When God has gifted all the

members of the congregation to help grow disciples, why should we silence

the contribution of all but one of them (the pastor), and think that this is

sufficient or acceptable?

In his fine book on preaching, Speaking God's Words, Peter Adam

conducts a detailed survey of the ministries of the word in the New

Testament, together with a consideration of the ministry practices of John

Calvin, Richard Baxter and ministries in our churches today. He concludes

that:

…while preaching… is one form of the ministry of the Word, many

other forms are reflected in the Bible and in contemporary Christian

church life. It is important to grasp this point clearly, or we shall try and

make preaching carry a load which it cannot bear; that is, the burden of

doing all that the Bible expects of every form of ministry of the Word.

[3]

Adam goes on to define preaching as the "the explanation and application

of the Word to the congregation of Christ in order to produce corporate

preparation for service, unity of faith, maturity, growth and upbuilding".[4]

But he points out that Sunday preaching is not the only way to address the

edification of the body:

While individuals may be edified in so far as they are members of the

congregation, there may well be other areas in which they need

correction and training in righteousness which they will not obtain

through the Sunday sermon, because by its very nature it is generalist in

its application.[5]

Well, you may ask, what is being suggested—that as well as a 25-minute

sermon, we have 50 one-minute testimonies from the congregation?

That might make for a fascinating and encouraging (if rather long) Sunday

morning, but that is not what we're proposing. Because Sunday is not the

only place where the action is. This is something that one of the great gospel

ministers of our Reformed-evangelical heritage knew very well.

The example of Richard Baxter

The name of Richard Baxter will forever be associated with his classic

work The Reformed Pastor. Interestingly, by 'Reformed', Baxter did not

mean a particular brand of doctrine (although his own somewhat

idiosyncratic theology was certainly 'Reformed' in that sense), but rather a

ministry that was renewed and renovated, and that abounded in vigour, zeal

and purpose. "If God would but reform the ministry," Baxter wrote, "and set

them on their duties zealously and faithfully, the people would certainly be

reformed".[6]

Baxter's remarkable ministry among the 800 families of the village of

Kidderminster began in 1647, and transformed the parish. His strategy of

pastoral ministry was formed during the chaotic vacuum of ecclesiastical

authority and discipline following the English Civil War and the failure of the

Westminster reforms. Baxter wanted to ensure that every parishioner

understood the basic tenets of the faith and the godly life, and The Reformed

Pastor, published in 1656, consists of an extended exhortation to his fellow

ministers to conduct a ministry that is not merely formal, but personal and

local.

In calling for this reformation of ministry and church life, Baxter's chief

motive was the salvation of souls: "We are seeking to uphold the world, to

save it from the curse of God, to perfect the creation, to attain the ends of

Christ's death, to save ourselves and others from damnation, to overcome the

devil, and demolish his kingdom, to set up the kingdom of Christ, and to

attain and help others to the kingdom of glory".[7]

This overriding and confronting challenge to the conversion of souls

permeates each section of The Reformed Pastor—whether speaking about

the pastor's oversight of himself or his oversight of the flock. This, Baxter

had come to believe, was the true cause and agenda for reformation of the

church. It could not be achieved merely through structural changes:

I can well remember the time when I was earnest for the reformation of

matters of ceremony… Alas! Can we think that the reformation is

wrought, when we cast out a few ceremonies, and changed some

vestures, and gestures, and forms! Oh no, sirs! It is the converting and

saving of souls that is our business. That is the chiefest part of

reformation, that doth most good, and tendeth most to the salvation of the

people.[8]

In Baxter's view, if the ministry was going to be reformed to focus on the

conversion of souls, pastors had to devote extensive time to "the duty of

personal catechizing and instructing the flock". He saw personal work with

people as having irreplaceable value, because it provided "the best

opportunity to impress the truth upon their hearts, when we can speak to each

individual's particular necessity, and say to the sinner, 'Thou art the man'".

[9] Public preaching was not enough, according to Baxter. In fact, he went so

far as to say "I have no doubt that the Popish auricular confession is a sinful

novelty… but our common neglect of personal instruction is much worse"!

[10] It was only through personal catechizing that Baxter could find those

who:

…have been my hearers eight or ten years, who know not whether

Christ be God or man, and wonder when I tell them the history of his

birth and life and death as if they have never heard it before… I have

found that some ignorant persons, who have been so long unprofitable

hearers, have got more knowledge and remorse in half an hour's close

discourse, than they did from ten years public preaching. I know that

preaching the gospel publicly is the most excellent means, because we

speak to many at once. But it is usually far more effectual to preach it

privately to a particular sinner.[11]

Elsewhere, Baxter wrote:

It is but the least part of the Minister's work, which is done in the

Pulpit… To go daily from one house to another, and see how you live,

and examine how you profit, and direct you in the duties of your

families, and in your preparation for death, is the great work.[12]

Baxter worked hard to convince others of the need for this kind of

ministry reformation. He formed the 'Worcester Association' to promote the

cause, members of which embraced the commitment to know personally each

person in their charge—a challenging commitment even now, but

revolutionary in Baxter's time.

Sadly, however, Baxter's example was "widely hailed, less widely

followed, and finally, perhaps more often than not, simply abandoned…"[13]

Certainly, not many pastors today walk in his footsteps, even though they may

have read The Reformed Pastor at some point in seminary and nodded

approvingly. The idea of personal ministry alongside preaching ministry is

admirable and hard to disagree with. It is also thoroughly biblical. Paul says

to the Ephesian elders that he "did not shrink from declaring to you anything

that was profitable, and teaching you in public and from house to house"

(Acts 20:20). The location for word ministry is necessarily public, but it is

also inescapably personal and domestic. According to Baxter, this is the only

way we can fulfil Paul's powerful exhortation to those same elders: "Pay

careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit

has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained

with his own blood" (Acts 20:28).

Given that our context is undeniably very different from Baxter's—

culturally, politically, socially, educationally—how do his insights inform

our understanding of ministry? There are four key challenges:

• Evangelism is at the heart of pastoral ministry. Ministry is not about

just dealing with immediate crises or problems, or about building

numbers, or about reforming structures. It is fundamentally about

preparing souls for death.

• Ministers need not be tied to traditional structures but should use

whatever 'means' (Baxter's term) available to call people to repentance

and salvation. For Baxter, this meant not being tied to the pulpit, but

also going into people's houses to instruct and exhort them.

• We should focus not only on what we are teaching, but also on what

the people are learning and applying.

• In many respects, in our era of widespread education, there is even

more scope to implement Baxter's vision of personal catechizing. In

many parts of the world, there is now a highly-educated laity who can

not only learn well, but also very ably teach others. The personal houseto-

house discipling can be done not only by the pastor, but also by the

disciple-makers that the pastor trains.

One of the first steps in applying these challenges is to conduct an honest

audit of all your congregational programs, activities and structures, and

assess them against the criteria of gospel growth. How many of them are still

useful vehicles for outreach, follow-up, growth or training? Is there

duplication? Are some structures or regular activities long past their use-by

date? Saying 'yes' to more personal ministry almost always means saying

'no' to something else.

However, even freeing up some time in the diary may still leave us

feeling swamped with the amount of 'people work' there is to do. That's why

we need co-workers.

[1] See G Hawkins and C Parkinson, Reveal: Where Are You?, Willow Creek Resources,

Chicago, 2007.

[2] For further thinking about small groups and how they can be positive vehicles for gospel

growth, see Colin Marshall, Growth Groups, Matthias Media, Sydney, 1995.

[3] Peter Adam, Speaking God's Words: A Practical Theology of Preaching, IVP, Leicester,

1996, p. 59.

[4] Adam, p. 71.

[5] Adam, p. 71.

[6] Richard Baxter, Reliquiae Baxterianae, ed. M Sylvester, London, 1696, p. 115, cited in JI

Packer, A Quest for Godliness, Crossway Books, Wheaton, 1990, p. 38.

[7] Richard Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, 5th edn, Banner of Truth, London, 1974, p. 112.

[8] Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, p. 211.

[9] Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, p. 175.

[10] Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, pp. 179-80.

[11] Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, p. 196.

[12] Baxter, The Saints' Everlasting Rest, sig. A4, cited in J William Black, Reformation Pastors:

Richard Baxter and the Ideal of the Reformed Pastor, Paternoster, Milton Keynes, 2004, p. 177.

[13] Black, Reformation Pastors, p. 105

Comments

Post a Comment